Allie Vibert Douglas made history when she earned her PhD at McGill.

It was 1926 – a time when higher education wasn’t an option for most women.

By then, Douglas already had a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Science from McGill – and had been named a member of the Order of the British Empire for her wartime service. With her PhD, she became the first Canadian woman to obtain a doctorate in astrophysics.

Douglas received accolades during her lifetime and posthumously, including an honorary degree from McGill in 1960. The National Council of Jewish Women of Canada declared Douglas one of 11 Canadian ‘Women of the Century”. An asteroid and a crater on Venus bear her name. Yet you could easily make the case that Douglas should be better known.

Physics Professor Victoria Kaspi, the Director of the Trottier Space Institute, hopes to shine a light on the trailblazing astrophysicist. Kaspi has generously established a new student award for the top PhD thesis in astrophysics at McGill and named it after Douglas, who died in 1988.

A gathering to celebrate the first awarding of the Dr. Allie V. Douglas Prize was held at the Trottier Space Institute in May. Eight of Douglas’s relatives attended as well as the inaugural recipient of the prize, Dr. Hope Boyce, MSc’18, PhD’23, and her PhD supervisor Professor Daryl Haggard.

The prize is to be given to the top PhD thesis regardless of the student researcher’s gender, Kaspi notes. “But I love that it’s starting with a woman which is an echo of Professor Douglas’s achievements and also a reflection of how far women have come both in astrophysics and science.”

Kaspi told the group she first learned of Douglas from colleague Jean Barrette, now Emeritus Professor, who had pored over archival staff photos of McGill’s physics department and noticed that Douglas had a front-row seat alongside well-known McGill professors such as John Stuart Foster and David Arnold Keys.

“She did very interesting papers [at McGill], and I’m still puzzled why she was never promoted to professor,” says Barrette, who shared his findings with Kaspi.

Left to right: Professor Daryl Haggard, Hope Boyce, and Professor Victoria Kaspi. Award presentation at Trottier Space Institute on May 9, 2024.

“It became clear that there was this incredibly accomplished pioneer that I and no one else in the department knew about,” Kaspi says.

“I was fascinated to read that in addition to having published papers here in the Department of Physics with John Stuart Foster of the Foster Radiation Lab, I saw she had written a paper with Sir Arthur Eddington,” adds Kaspi, of the famous British astrophysicist. (Douglas also wrote a biography of Eddington, under whom she studied at Cambridge, and corresponded with Albert Einstein during her book research.)

“I was just shocked that somebody so accomplished and such a pioneer really had not been much recognized, particularly at our own university. The mists of time sometimes cover things up. So, I wanted to get rid of those mists,” says Kaspi of naming the prize after Douglas.

Kaspi is a world-renowned astrophysicist and the recipient of many honours herself, including the 2022 Albert Einstein World Award of Science and co-winner of the 2021 Shaw Prize in Astronomy.

“I wanted to somehow give back to the university that has supported my research,” Kaspi says. “I also wanted to find a way to give back to graduate students who really form the lifeblood of my research,” she adds. “They’re crucial to what I do.”

A prize can raise the international stature of a special thesis and is something a student can put on their CV. “It seemed to me it was a fitting way to recognize and remember [Douglas’s] accomplishments while also supporting and promoting the careers of excellent McGill astrophysics research students,” says Kaspi.

Prize-winning thesis explored supermassive black holes

Hope Boyce is honoured by the recognition from the physics department. “I am extremely grateful to Prof. Vicky Kaspi, for her generosity, and my advisor Prof. Daryl Haggard, for her mentorship and for fostering such a supportive and enthusiastic environment in our group,” Boyce says. “Our projects would not have succeeded without her guidance, the dedicated efforts of my generous colleagues, and the support and kindness of my fellow graduate students. Together, our work in observational astrophysics has contributed some small amount to our collective understanding of nature, and I am very grateful to have had that opportunity.”

Boyce’s thesis explored the dynamics of material in the interior hearts of galaxies, explains her PhD supervisor Daryl Haggard, an associate professor of Physics – “in particular, material in what we would call the ‘sphere of influence.’ This is basically the region in the center of a galaxy that is under the gravitational influence of the supermassive black hole.”

One of the exciting pieces of Boyce’s thesis, adds Haggard, was participating in the discovery of the first image of the supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way – a global research effort involving more than 300 researchers in the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration.

“Hope was one of the key lead authors on our data paper which looked at this beautiful first image of the supermassive black hole. And then also what that looks like at multiple different wavelengths,” Haggard says.

“Hope’s unique contribution to this very large international collaboration was looking at those gas dynamics at a bunch of different wavelengths really down in the heart of the Milky Way.”

An enduring legacy

Nearly 100 years after Douglas obtained her doctorate at McGill, her legacy now lives on in the faculty where she lectured for many years but wasn’t put on a tenure track.

Born in Montreal, she and her brother were orphaned as children and raised by their maternal grandmother and aunts. Their aunt Mina Douglas, a trailblazer in her own right, was arguably the mother figure to both children, according to Stephen Douglas who came to McGill for the award presentation along with his siblings and other relatives. (Mina was the first woman to receive a diploma from McGill in 1877 and later co-founded what became Montreal’s Old Brewery Mission.)

Allie Vibert Douglas paused her McGill studies to work as a statistician in the War Office in London during the First World War, for which she was later honoured.

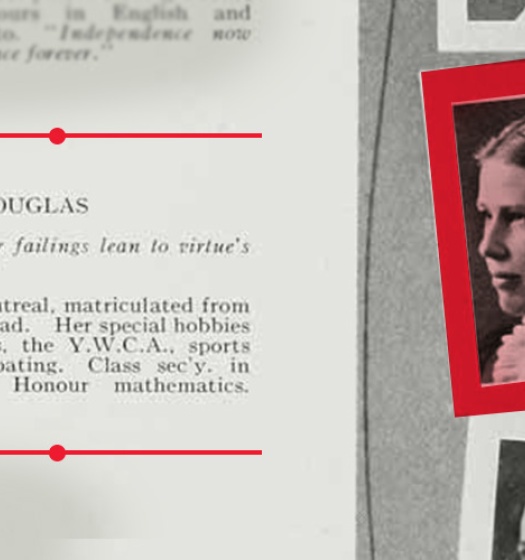

Allie Vibert Douglas’s 1916 Old McGill yearbook entry.

In 1939, after nearly two decades as a lecturer and demonstrator in McGill’s physics department, Douglas left McGill for Queen’s University where she was Dean of Women and also an astronomy professor. In addition, she led the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, the first woman to do so.

Douglas delivered public lectures, propelled by an interest in communicating science. In 1932, in advance of a total solar eclipse in Montreal, she co-authored a booklet for the public about the celestial event.

“She found an audience and developed a real skill in writing about science, and she did an Atlantic Monthly article,” her great nephew Stephen Douglas says.

He and his brother Dan expressed appreciation for the new award in their great aunt’s name. Their father, who passed away recently, “was very moved to have that happen,” says Stephen Douglas.

“It was incredibly generous and gracious, and just amazing of Dr. Kaspi to have done this,” says Dan Douglas. “We’ve always felt that Aunt Allie certainly deserved the recognition. She was incredibly supportive of students and she taught at McGill for quite a long time.”

“I think this award brings a recognition to all that she did.”