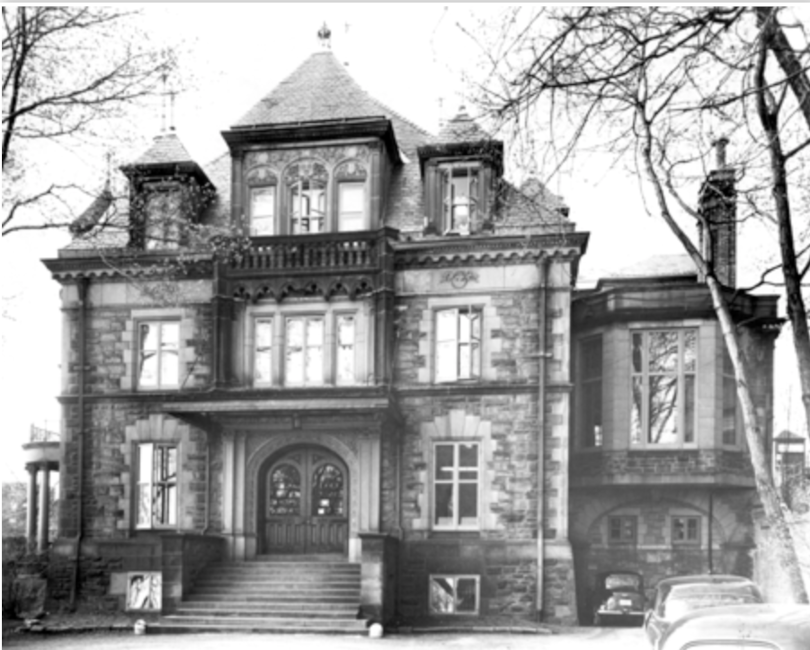

On Peel Street near the corner of Doctor Penfield Avenue in Montreal stands a magnificent limestone mansion with a long history.

Built in the French château style with two circular turrets and a central tower, Old Chancellor Day Hall is well known today as the home of McGill’s Faculty of Law. But 75 years ago, this building – then known as Ross House – was the site of a legendary dance performance that shook up Quebec’s cultural scene.

Shortly before the building was donated to McGill in 1948, an up-and-coming Montreal artist named Françoise Sullivan, DLitt’23, had set up a dance studio there and was teaching classes.

Sullivan and her friend Jeanne Renaud put on a dance recital at Ross House in the spring of 1948 that explored improvised movement and simple expressive gestures. The recital, which included a groundbreaking solo performance from Sullivan called Black and Tan, is now widely considered to be the first modern dance presentation in Quebec.

Exterior of Chancellor Day Hall (formerly Ross House), circa 1950.

A few months after the recital, Sullivan was one of the signatories of the Refus global, an anti-establishment manifesto that challenged traditional values and later ushered in the Quiet Revolution in Quebec.

“In dance today we see a return to the magic of movement, to natural and subtle human forces. Dance today aspires to exalt, to charm, to hypnotize – to wholly engage the sensibility,” Sullivan wrote in her contribution to the Refus global, an essay entitled “Dance and hope” which laid out her conception of modern dance.

Sullivan went on to become a prolific artist known for her remarkable ability to move freely between different mediums and disciplines: dance, painting, photography, and sculpture. Today she is recognized as a pioneering figure in Canadian art and still paints every day.

In honour of her 100th birthday in June 2023, Montrealers have been celebrating Sullivan’s life and works throughout the year – namely through a 21,000 square-foot mural on Saint-Hubert Street and an exhibition showcasing her most recent paintings at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

In addition to awarding her an honorary doctorate this past June, McGill is paying tribute to the living legend through the acquisition of one of her artworks for the University’s Visual Arts Collection.

This acquisition was made possible by the Faculty of Law and a group of private donors committed to honouring Sullivan’s legacy and connection to McGill: Paul Frazer, BA’70; Ronald Harvie, MA’94, PhD’99, and Douglas Baguley; Robert Graham, BA’73, MA’89; Gwendolyn Owens; Katherine Smalley, BA’67; and Steven Spodek, BA’79, BSW’87, MSW’95.

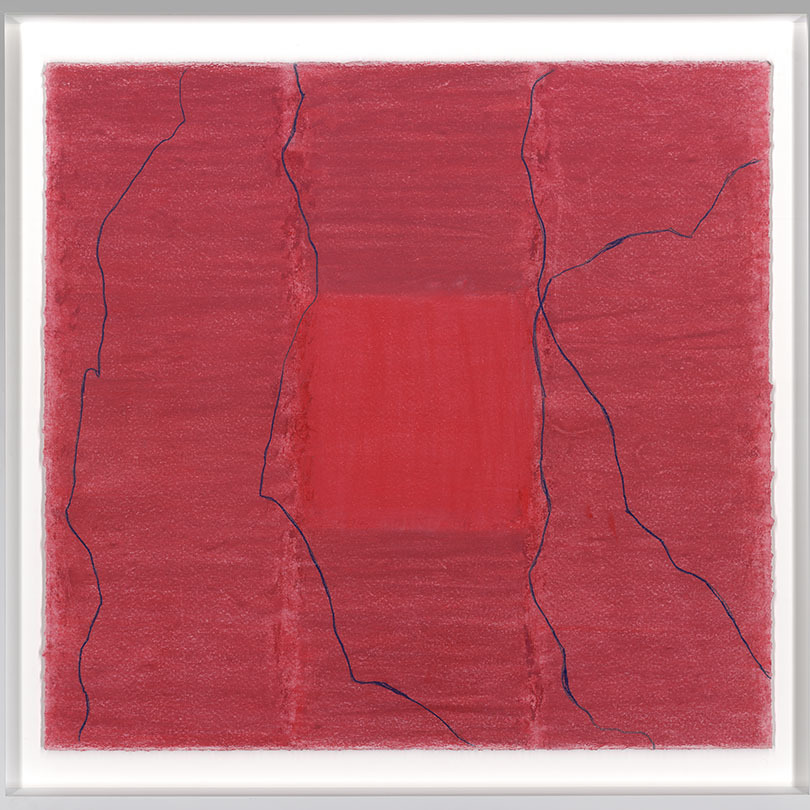

Gwendolyn Owens, Director of the Visual Arts Collection, explains that the Untitled work is part of series of pastels from 1999 that Sullivan rediscovered recently while moving to a new studio space.

“The place it needs to be is in the Faculty of Law,” says Owens, adding that the piece will soon be installed in Old Chancellor Day Hall as an homage to Sullivan’s trailblazing influence on modern dance.

Dancing lines on pastel

The acquisition was chosen by staff and students who work at the Visual Arts Collection (VAC). Honours Art History student Jocelyn Campo was both stunned and excited to be invited to participate in the selection process during a donor-funded internship at the VAC.

“It was my first day and we all piled into an Uber and drove down to the gallery together,” recounts Campo. She was part of a delegation from the VAC that visited the Simon Blais Gallery to examine a portfolio of Sullivan’s pastels.

“I couldn’t decide what was more fun to look at: the artworks or the interns gasping every time we turned the page to look at a new one,” says Michelle Macleod, the VAC’s assistant curator.

After much deliberation, the group decided on a 30x33-inch vivid pink pastel on paper, with thin indigo lines that travel vertically across the work.

“Françoise is known for those beautiful large-scale paintings that are so rich in colour. Her palette is just fabulous, so we wanted to have that punchy colour,” says Macleod.

“When you get really up close to it, there's all this texture because she layered the pastels and it has tons of dimension,” Campo adds.

Françoise Sullivan, Untitled, 1999, Pastel on Paper. Gift of Paul Frazer, Ronald Harvie, Douglas Baguley, Robert Graham, Gwendolyn Owens, Katherine Smalley, Steven Spodek, and The McGill Faculty of Law. McGill Visual Arts Collection, 2023-046.

“We were really drawn to these lines dancing on top of the pink colour,” says Macleod. “They evoked the beautiful movement of modern dance and creating new forms with the body, which is especially important when we're thinking about Françoise Sullivan’s impact here at McGill and connecting her expression in modern dance in the 1940s with her visual production.”

Françoise Sullivan and the Automatistes

Sullivan was one of the founding members of the Automatistes, a group of avant-garde Quebec artists led by abstract painter Paul-Émile Borduas who penned the Refus global. Influenced by the French Surrealist movement, the group rejected established artistic traditions and experimented with spontaneous or “automatic” approaches to creative expression.

“The idea [behind Automatism] is that any practitioner or novice can quiet the waking consciousness of the rationalized workaday world in order to sabotage productivity and the work ethic and allow access to the fluid unconsciousness during the day,” explained art historian Abigail Susik at a lecture put on by the McGill Library to mark Sullivan’s 100th birthday.

“What Françoise Sullivan does is update and improve Surrealist Automatist efforts, activating them from the identity standpoint of a young female working in the northern reaches of North America,” said Susik, who is a Professor of Art History at Willamette University in Oregon.

Françoise Sullivan

Susik’s lecture, entitled Trance, Dance and Surrealism: Françoise Sullivan and Les Automatistes in World War II-Era Montreal, took place at Moot Court in New Chancellor Day Hall on November 16 (watch the full recording here).

With Françoise Sullivan present in the audience, not far from where her dance studio would have been in the late 1940s, Susik spoke about Sullivan’s cultural impact and shared insights from a recent interview with the artist.

When asked to comment on the University’s acquisition of a Françoise Sullivan pastel, Susik pointed out connections with Sullivan’s Automatistes roots.

“The line is really interesting to me,” says Susik, reflecting on the Untitled pastel. “It reminds me of this question of the automatic drawing, where the artist is not so much focused on where the line is going or what they're drawing but rather allowing the hand to wander and move.”

“We have to think of Françoise as a dancer, so a wandering line allows the artist to experience the mark making as a kind of flowing gesture of movement.”

Art, motherhood and inspiration

At the lecture, Susik revealed that she and Sullivan have connected on a personal level about balancing motherhood and creative work.

Sullivan took a break from art in the 1950s, finding it difficult to continue her dance and choreography career while raising four children. She began experimenting with sculpture in 1959 as a medium that would allow her to work from home and be with her sons, while continuing to push artistic boundaries.

“She probably had to have a conversation with herself, saying: No, I need this, this is possible, I'm going to do it,” says Susik.

“In general, as women we have to remind ourselves of our own value, and [Sullivan] has done that for me. Just looking at who she is as a person is a way of learning how to function in this society as women and as mothers and as artists all at once.”

Owens explains that the decision to acquire one of Sullivan’s works is also part of an effort to diversify the range of artists represented in the Visual Arts Collection. “This is a woman artist with a close connection to a space at McGill, so it’s something that should be in this collection,” Owens says.

“I think any new artwork acquisition – any donation like this – helps the Visual Arts Collection with our mandate,” says Macleod. “It's really a mission to activate the art collection as a resource, whether that's for study or for mental health or for inspiration.”